STRANGE PASSING STRANGE

UNEARTHING THE FORGOTTEN WORKS AND WORLDS OF HERBERT CROWLEY

As narratives and histories are repeated over the years, they simultaneously solidify and warp. A false statement can become part of the official record; a minor detail magnified through retelling can become a central focus. And histories always contain omissions – facts which were once widely known become lost in the march of time, subsumed by bigger stories, or simply lost in the musty corners of the attic. There are untold numbers of vital historical secrets hidden everywhere, waiting to be discovered and rediscovered -- artworks and documents which can give greater clarity to our present moment, and shed light on the human condition as clearly now as they did decades, centuries, or eons ago.

|

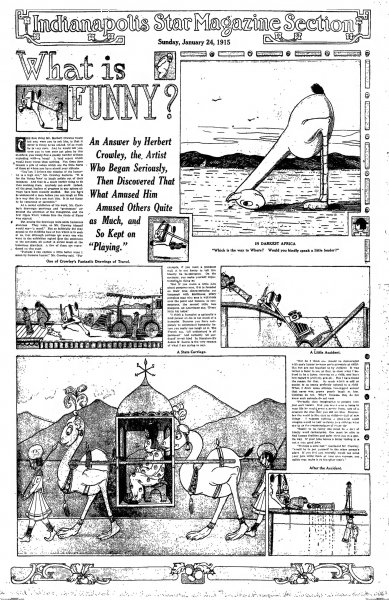

|||

| Recorte de prensa, acompañado con ilustraciones de Crowley, en el que el autor daba su visión sobre el humor. |

Herbert E. Crowley and the visionary work he created from the early 1900s through the mid 1930s certainly fits this bill. His work was never truly widely known, but Crowley was not entirely obscure in his time. He was at the locus of the early 20th century avant garde, and his artistic and intellectual circles included figures responsible for seismic shifts in explorations of art and the human psyche. Crowley crossed paths with James Joyce, Rabindranath Tagore, and Peggy Guggenheim. He formed a close relationship with C.G. Jung, who described Crowley as being “driven in to astounding depths” in his art-making, declaiming that his work explored “the multiple luminosities of the collective unconscious.” Crowley created a body of work which manages to look contemporary – and even futuristic – over a hundred years later.

Herbert Crowley exhibited work in the paradigm-shifting 1913 Armory Show [1]. He was closely involved with the early days of experimental theater in New York via his wife-to-be Alice Lewisohn. His one-of-a-kind comic strip ran for a brief fourteen weeks in the groundbreaking Sunday comics section of the New York Herald in 1910. The Sunwise Turn bookstore, a hotbed of intellectual and political foment founded in 1916, often exhibited his work. Crowley would join Sunwise Turn owner Mary Mowbray-Clarke and her husband John (one of the principle organizer of the Armory Show) in founding The Brocken, an artist’s colony in rural Pomona NY, which hosted and nurtured a virtual who’s-who of cultural luminaries during the modernist era. Crowley’s frequent exhibitions in New York during this period (including a 1914 joint show with Léon Bakst) received near unanimous glowing praise in all the major newspapers and art periodicals of the day.

All in all, it’s apparent that Herbert Crowley had some effect on the shape of the creative landscape of his era. Though he was something of a background figure even during his heyday, his strange influence surely echoed down through the decades even as his name and work were forgotten.

My own first exposure to Crowley’s work came about in 2008. I was traveling as a musician and sleeping on a friend’s floor in Blacksburg, Virginia. While perusing my friend’s impressive collection of art books, I came across Art Out of Time, Dan Nadel’s 2006 collection of work by “unknown comics visionaries.” The book compiles the creations of cartoonists whose reputations had either faded or had never been widely known. It’s a sort of alternate history of comics, and all of its contents are at least relatively obscure. Leafing through the book, I was delighted that such a trove of forgotten work was collected and brought to light.

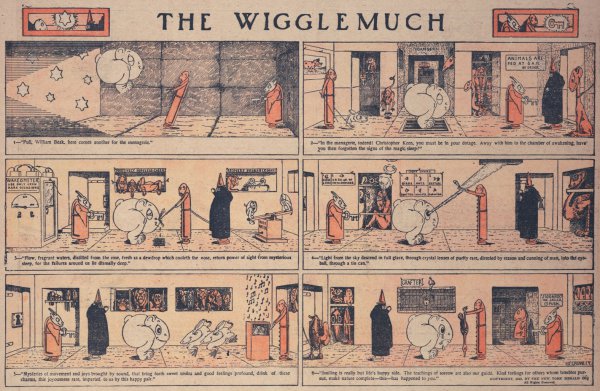

I stopped in my tracks when I arrived at The Wigglemuch, a perplexing comic strip that stood out as being anomalous in a collection of anomalies. It explored themes of mysticism and the nature of existence through flat, paper doll-like characters. The text was supplied in rhyming couplets placed below each panel. It was dense and seemed to be full of some hidden meaning. It combined ethereal design with creatures that Nadel insightfully described as “more akin to mandalas than any cartoon character.” In short, I was awed by this work. I immediately felt as if it was on par with any of the greatest artwork I’d ever seen.

|

| Novena plancha de The Wigglemuch, publicada en el New York Herald el 15-V-1910. |

I wanted to see more, and to learn more about the artist. I assumed there would be at least a small cult following for Herbert Crowley – that perhaps he was known as an outlier of symbolism, or a devotee of Theosophy who dipped his toe into the world of newspaper cartooning in the early days of the medium. Flipping to the back of the book, where there were short biographies of each artist, I was astonished to see that Herbert Crowley’s birth and death dates were unknown. Nadel wrote that he represented the “single largest information gap in this book,” – a book about unremembered artists – and that aside from the existence of the comic strips, “nothing else is known about Crowley or his work.”

Throughout the months following my exposure to this otherworldly portal I would periodically check online to see if anything related to Herbert Crowley had appeared. Nadel continued his research, updating his blog with several posts about Crowley. In February 2010, Nadel wrote that he had been contacted by Crowley’s neice, who filled him in with some biographic details, and shared some of his sketchbooks and ephemera. Nadel included some tantalizingly blurry photos of gorgeous unseen artwork, and some indication that more was to come, writing “Now, when I published Art Out of Time, I knew nothing, not even birth and death dates. I know a whole lot more now, and as I learn yet more I’ll update you, my tiny, tiny public.” “Crowley wrote complex symbolic tracts to accompany his images.” “Crowley was deeply interested in morality, spiritualism, and apparently, was a dedicated Jungian. More on that enticing connection later.”

I was more intrigued than ever. I wanted so badly to pore over the “complex symbolic tracts” and to learn about the enticing connection to Jungian psychology. But “later” never came. Month after month went by, and almost every day I would wonder about Herbert Crowley, imagining all the things he could have been connected to, wondering what his life and world were like, what kind of person he must have been in order to be able to create something as singularly weird and wonderful as The Wigglemuch. I began to think I would need to launch my own investigation.

My first order of inquiry was the Billy Ireland Cartoon Research Library at Ohio State University. Most of the Wigglemuch strips in Art Out of Time were sourced from their collection, which was founded on the collection of legendary comics archivist Bill Blackbeard, who salvaged literal tons of newspaper comics sections from incineration while libraries were busy purging themselves of newsprint during the great microfilming craze of the late 1960s.

I drove out to Ohio in 2010 to visit their archive and view the Wigglemuch strips in their original format. As it turned out, their collection was missing the first and last of the strips, but they had stunning examples of installments two through thirteen. I photographed them as best I could with my hand-held camera, but thought it was such a shame that they hadn’t all been digitally archived yet. The experience led me to redouble my dedication to uncovering everything that could be found about Crowley and his work

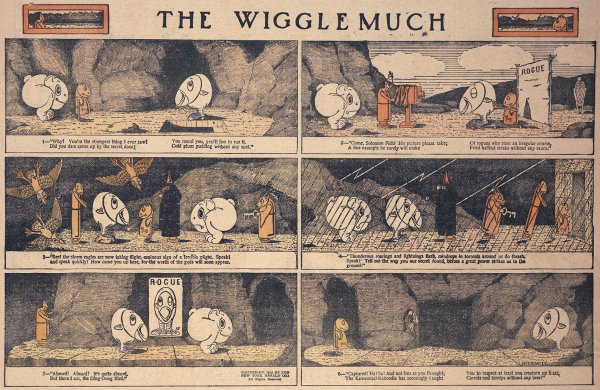

The strip followed the adventures of a magical creature called the Wigglemuch[2]. It’s never made clear whether Wigglemuch is the name of the individual animal, or of the species. Crowley took several weeks to settle into how to write the title – the early strips are called “The Wiggle – Much,” then “The Wiggle Much” and finally “The Wigglemuch.” There’s a sense of improvisation in the work that is fascinating to watch unfold. With each passing week the strip grows more abstract, and becomes more focused on exploring philosophical quandaries. The text also gradually changes from simple narrative captions to rhyming couplets. The Wigglemuch is pursued through various netherworld realms – underground caverns, mountaintop temples, ancient castles – and the quality of the strip, both in regards to draftsmanship and imaginative inventiveness seems to increase with each episode. To see these incredibly rare works in their original newsprint format was an awe-inspiring experience. I wondered if the Wigglemuch had continued for years instead of for weeks if it would today be remembered alongside visionary comics classics such as Krazy Kat… but for whatever reasons, it was not to be. It was and remains a radiant relic of something that just barely was, and a tantalizing indicator of an alternate path that could have been – but wasn’t – taken by the comic strip format. There was, however, a cache of Crowley’s work still extant in the world, including the never-published single-panel further adventures of the Wigglemuch.

|

| Next page, 1910, 22-V. |

In the 2009 blog post, Dan Nadel also mentions off-hand that “…the Met has some works on paper of his in storage that I have, to my shame, not gone to request, but beyond that, well, I cast wide nets, but don’t tend to dig deep holes. But in this case I should.”

Following this lead, I decided to try to dig the deep holes. I expected to uncover a few scraps of Crowley’s work at best. New York isn’t far from my home in Philadelphia, so my wife Mandy and I arranged an appointment at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see what they had.

I expected to uncover a few scraps of Crowley’s work at best; instead I found a vast wealth of material. Several heavy boxes stored in the prints and pictures department contained a treasure-trove of newspaper clippings, doodles, the original artwork for most of the comic strips, including unfinished, never published plans for Wigglemuch episodes fifteen and sixteen. There was also a hefty stack of heart-stoppingly detailed filigree drawing, clippings of reviews, and lots of names to follow up on – names of people who had donated materials, who were connected to Crowley, who had helped with his career, or impacted his life.

|

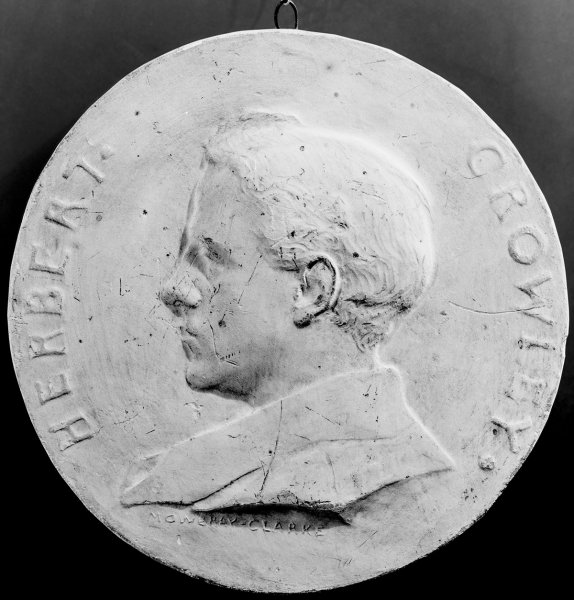

|

| Parte del material encontrado en el Metropolitan Museum of Art: una ilustración donada por Alice Lewisohn (1946), y un medallón realizado por John Mowbray-Clarke en 1908. |

Aside from this, we also uncovered a 1914 exhibition catalog, and many newspaper articles mentioning Crowley, or describing his work in the context of the time. He was often compared in the press of the day to William Blake or Aubrey Beardsly, and was seen as developing a "new, and perhaps unique, form of art." The material in the Met was donated in 1946 by Alice Lewisohn, whose contributions formed the basis of the Met’s costume department. The Lewisohn sisters were noted theater producers in New York, and have traveled the world collecting costumes and studying dance. It seems as if Herbert Crowley’s work was donated as an “extra” along with the costume materials.

Returning home, Mandy and I were both reeling from the experience. Crowley’s genius went further than we had realized. Deeper research unveiled deeper mystery.

I decided it was now a ripe moment to finally send an email to Dan Nadel. I composed an over-long and probably over-enthusiastic letter about my research, and emailed the address listed on his blog. I didn't receive a reply – yet. But this journey had barely begun.

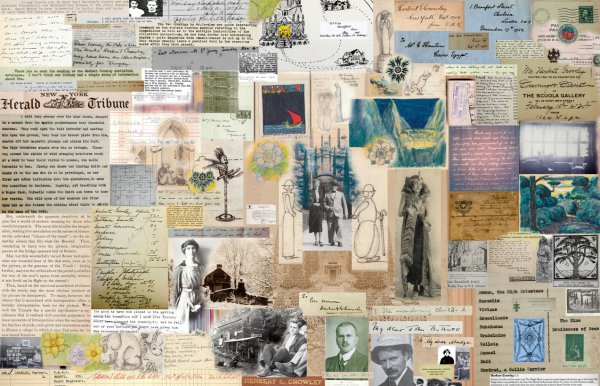

|

| Collage que contiene parte del material encontrado a lo largo de muchos años de investigación. |

In November of 2010 I discussed the Wigglemuch with my friend Billy Brett who I knew from my years as a touring musician. Billy shared my passion for The Wigglemuch -- and he happened to work at a school library. He was able get the New York Herald strips on microfilm via interlibrary loan.

We scanned the strips and eventually, in November of 2013, decided to put them online. We had given up on any grand ideas of a publishing project, and thought it would just be nice to share them with the world. This led to some unexpected break-through moments. The strips had apparently not yet landed in front of the right sets of eyes; now they would.

Billy and I created a blog post featuring the microfilm scans and some of my photos, and tweeted it out. The tweet took on some life, and soon the prominent nerd culture site Boing Boing featured the blog. Within a day I was getting phone calls from people who had seen the post.

Cartoonist Mark Beyer, an acquaintance from Albuquerque (and comics legend in his own right) sent me an email telling me he had “got an email from my old cartoonist friend Art Spiegelman. He sent me a link for Herbert Crowley's Wigglemuch comic strip. Then I noticed that you were the one who posted it. I was really surprised." Being a fan of Spiegelman's work since age thirteen, I was thrilled to think that our blog post had made such waves, and was being seen by people who were excited about it. The web was growing.

At last, the reverberations of the Boing Boing post reached Dan Nadel. He responded to an email Billy sent, and included the contact for Crowley's niece in Switzerland. I reached out to her via email, and we began a correspondence.

Finally, in November of 2014, Mandy and I visited her in Zurich. We stayed for two weeks, buoyed by her immense hospitality and enthusiasm while we dutifully scanned and photographed hundreds of notebook pages, sculptures, prints, and paintings in her family’s collection.

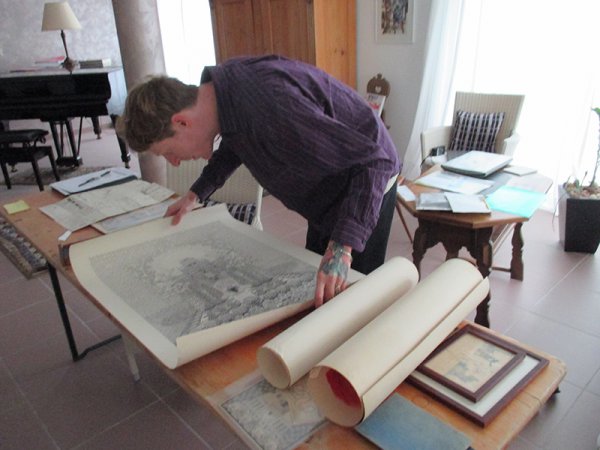

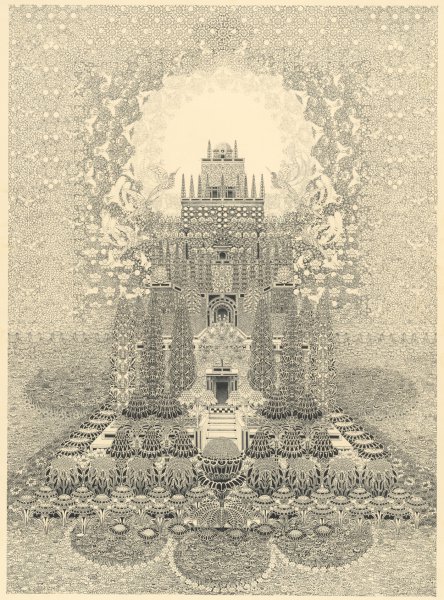

|

|

| Justin Duerr examinando el archivo de Crowley en Zurich. | Temple of Dreams (20 x 27 ¼ pulgadas), de la colección de Dwayne Bridges. |

We began to tie together more threads of Herbert Crowley’s story, including the end of his life. He and Alice Lewisohn became part of C.G. Jung’s inner circle after moving to Zurich in the late 1920s, and eventually this seems to have led to some stress in their relationship. Sometime around 1935 they were divorced, and Crowley re-married a woman named Wilhelmina Seilaz. “Mina” was a co-owner of a high end perfumery which had been frequented by Alice and Herbert. According to Seilaz family memory (Susi is Crowley’s niece via his second marriage) Crowley disavowed Jung’s influence after the divorce.

He was also apparently prone to emotional extremes, and would occasionally destroy his own creations. He appears to have gone through a severe crisis of this sort during his second marriage, and is reported to have renounced art-making, burning most of his drawings and paintings, and throwing his sculptures into a lake near his home in Ascona. He died at age 64 after less than two years spent married to Mina, on December 11, 1937.

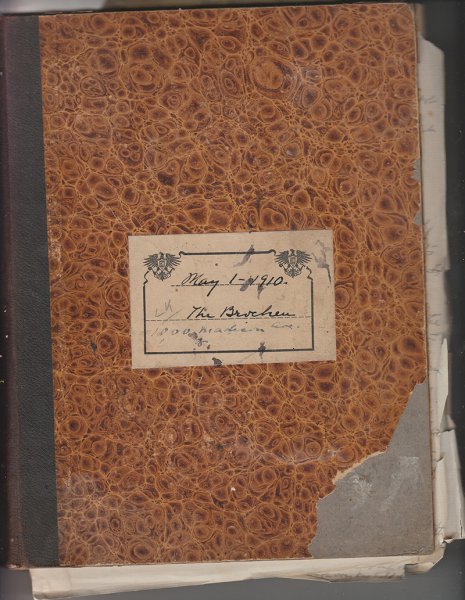

In March of 2015, I visited the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, and dug into their Sunwise Turn/Mary Mowbray-Clarke archive. I found many illuminating letters and pieces of ephemera detailing Crowley's involvement at the Brocken in the early teens. It was beginning to seem as if our investigation was more or less complete.

But we were on the verge of opening of a new door – a door which would lead to the most rewarding part of the research, and one of the single most magical experiences of my life.

My trip to Austin had convinced me of just how important The Brocken was to the Mowbray-Clarkes, as well as to Herbert and Alice. But, frustratingly, I hadn’t uncovered any photographic evidence of Crowley at The Brocken, despite his centrality to the early existence of the artists’ commune and retreat. My determination to find one led me to follow up on a loose end in M. Sue Kendall’s essay on Charles Burchfield’s artwork, in which she traces the influence of Mary Mowbray-Clarke and the Sunwise Turn on Burchfield’s life and career. Several photos in the essay were listed as being held by the Historical Society of Rockland County.

So, as my birthday approached that summer, Mandy proposed that we take a summer vacation trip and include the Historical Society on our itinerary. Perhaps they would know something about the original location of The Brocken. Maybe, if there was time, we could even visit the site.

|

|

| Material encontrado en The Brocken, incluyendo una hoja volante de Crowley. | Detalle de esta hoja: Sunwise Turn Broadside No. 4 (12 x 7.5 pulgadas) Colección de Janet Newman. |

Marianne Leese of the Historical Society was our tour guide on our visit to the Brocken in August of 2015. I’d read enough about the history of South Mountain Road that the winding drive seemed like a story come to life. We turned onto long meandering lane, passing under tall oak trees and a deep ravine. Finally we arrived at The Brocken. There, collapsed into the woods and overgrown with moss, were the very walls I’d seen in century-old snapshots. Small trees sprouted from decaying window frames, and stonework walls cropped up haphazardly. An old kitchen sink with tall plants growing in it sat in the midst of the tangle of weeds and vines, and, strangest of all, a two story fireplace shot straight up, the last remaining structure from the old 1700s house which hadn’t fallen into the woods. Several very beautiful tiles remained set in crumbling, mossy plaster, but the kitchen door itself remained only as a frame, like a piece of ancient, teetering driftwood ready to collapse with the next stiff breeze.

I imagined all the late-night talks that had taken place in front of these hearths – Herbert Crowley singing his songs, the planning of the 1913 Armory Show, untold numbers of artists and dreamers and misfits whose lives were profoundly touched by this place. The 18th century cemetery, nestled among the trees, was the final touch to give the place an atmosphere of profound sanctity.

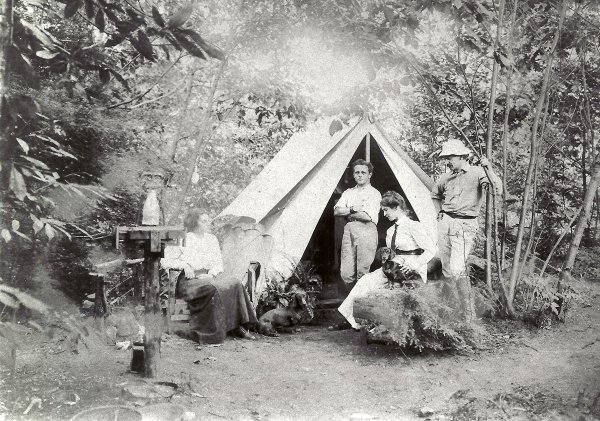

|

| The Brocken en sus comienzos. Herbert Crowley en el centro, Mary y John Mowbray-Clarke a la derecha. |

The newer section of the house was not entirely collapsed yet. It was an Art Deco brick structure built in a similar style to Mary’s famed Dutch Garden at the Rockland County Courthouse, a WPA project she headed in the early 1930s. In spite of a significant amount of water damage, the exterior structure looked firm. The door was open, partially falling off its hinges.

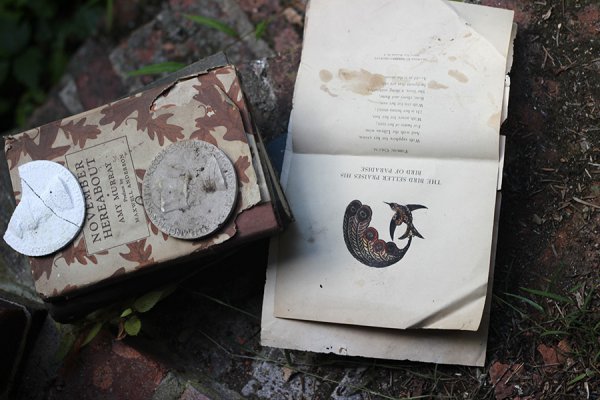

I was awestruck upon entering. Dim light from the cobwebbed windows fell on some rusty springs, from one of the old mattresses the Mowbray-Clarkes kept in the lean-tos and tents. Scattered all around the small sitting room, which still housed some decaying furniture and a very old piano, were an array of books and papers. A quick glance at a few of the books indicated that they had belonged to Mary and other Brocken residents of the old house. Mandy picked up one at random, and flipped it open: a 1902 edition of Kropotkin’s “Mutual Aid,” a book which Mary had called a “guiding light” in one of her diaries. There was a copy of poet Amy Murray’s book “November Hereabout” with a Gaelic inscription to Mary. Such discoveries seemed unending.

|

|

|

Aspecto actual de The Brocken: entrada por la zona menos derruida de la casa, puerta de la cocina y el piano en el interior.

As we exited the room, something caught my eye on the brickwork steps leading outside. A small white, round object, broken in two pieces, lay near the path to the lane. Picking it up, I realized it was one of John Mowbray-Clarke’s plaster medallions. It was almost entirely eroded by rainwater due to being outside, and tiny specks of moss dappled its water-pocked surface. I was moved by the striking sight of this forgotten work literally returning to the earth.

As we continued to poke around the ruins, a neighbor happened by, and we began chatting. Her name was Janet Newman; she had moved to South Mountain Road in the 1950s, and had met Mary Mowbray-Clarke near the end of her life. She told us that she had salvaged several boxes of materials that had literally fallen out of the house as it decayed. She was currently en route to an appointment, but offered to show them to us another time.

I was beside myself at having been so lucky to chance across all of this – it was starting to seem as if I may actually find a lost Herbert Crowley artwork, or at least a letter or photograph. Later in the evening we decided to take another look inside the house, and immediately noticed an envelope on the floor which we hadn’t seen before. Picking it up, I noted the postmark: August 19, 1913. The contents detail a sordid affair at The Brocken. In part: “[…] Mr. and Mrs. Clarke should be told the story: that The Brocken was not a fit place for me to be as Mr. Clarke was making love to me and for that reason wanted Mr. Gorski off the place, that Mrs. Gorski was going to respect this story, and that he had already told three people. This I am willing to swear to before an attorney. – Shirley M. Sullivan.”

After discovering this and a few other interesting books, I went outside to eat and daydream among the haunted ruins. But soon I heard Mandy’s voice behind me: “Happy birthday Justin -- look at this!”

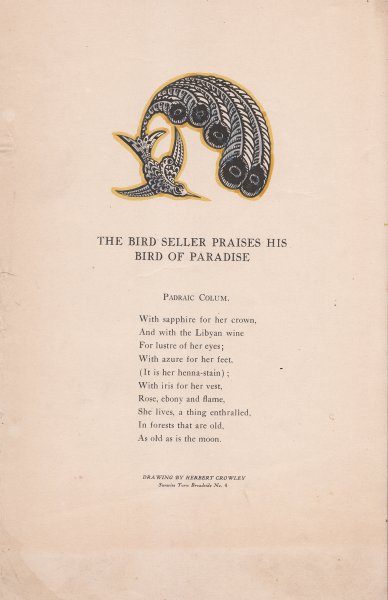

It was a hand-colored print by Herbert Crowley! Sunwise Turn broadside number four – an illustrated poem by Padraic Colum. She’d found it in a crate which had been doubling as a raccoon nest.

|

|

Diseño de Crowley y decorado definitivo de la representación de The Kairn of Koridwen.

There were also several half-decayed pages from what seemed to be a sort of fictionalized memoir of the early years of The Brocken. We found a few incredible old photographs (though none of Herbert), and as night started to fall, I became curious about the attic crawlspace – but we didn’t have anything tall enough to stand on to access it. It appeared to be full of moth eaten paper and moldy fabric, but while we were searching, one scrap of paper detailing Mary’s notes on color theory blew down from the opening. Who knew what undiscovered treasures lay mouldering away up there?

So Mandy and I planned a return trip, to view Janet Newman’s collection of Mary’s papers, and to explore the mysterious attic. I felt like I had found a portal into a past that one could palpably feel in the bones of the building, and in the woods and air around it. It was as though that these people and this place wanted their stories to be told, and I was overwhelmed with gratitude for the opportunity to act as the conduit between these two worlds.

We returned in the fall, and visited Janet. Janet Newman shared her memories about Mary and South Mountain Road, and loaned us some papers for study. I asked her if she had any of Mary’s old diaries. She told me that they were likely in an apartment on St. Marks Place in New York, with a person named Harry, who had lived there with Mary Mowbray-Clarke’s granddaughter Sandy. She gave me Harry’s address. By this time, we had run out of daylight – the attic would have to wait.

On my way home from a trip to the Metropolitan Museum to request photography of the Herbert Crowley work in their archive, I decided to try visiting the address that Janet had given me. I was unexpectedly seized with a case of nervousness upon seeing the nameplate on the door buzzer of the apartment – “Mowbray-Clarke.” Mary and John had become mythic figures to me, and seeing their name in a contemporary apartment building felt like getting a phone call from a character in a book.

|

|

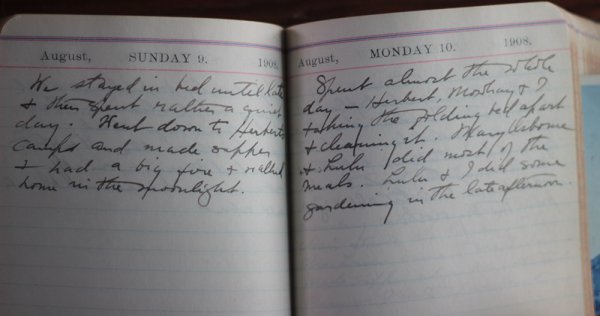

El diario de Mary Mowbray-Clarke's 1908, describiendo la vida en The Brocken.

I held my breath and rang the bell. Waited. Rang again. Almost relieved, I began to walk away, but then heard some noise at the door behind me. An elderly man creaked the door open. Harry! I did my best to quickly explain my research project, and told him that I was searching for the diaries of Mary Mowbray-Clarke. Harry was a bit hard of hearing, and communication was challenging. But he listened patiently and eventually shook his head. “No… nothing like that here. Sorry. Jethro [Mary’s great-grandson] might have them. I can give you his number.”

I thanked Harry, and when I got home I tried the number to no avail. But I reached out to Janet again, and she was eventually able to get in touch with Jethro, who did indeed have the diaries, which spanned from the late 1800s through the 1930s. He agreed to meet us at Janet’s house. So Mandy and I took our third trip up that December.

The scope of the material Jethro brought with him was staggering. The diaries were a gold mine of first-hand accounts of Herbert Crowley and life at The Brocken. Jethro agreed to allow me to borrow some, including the volumes spanning from 1908 to 1912, and many relevant miscellaneous papers he had in his possession.

Then Mandy and I returned to the Brocken before dark, finally ready to take on the attic. I strapped on a dust mask and some gloves, and propped a ladder near the entrance to the crawl space. I squeezed inside, and found myself among mountains of papers -- mostly chewed up by water and silverfish, who were in a sort of paradise of pulp and moisture. The motion of my body was causing a miniature whirlwind of paper debris. I saw what could have been one of Crowley’s nightscapes, but it disintegrated before my eyes, and was lost. Several pictures in frames were completely rotted away – only the frames remained, and some sad limp pieces of canvas or paper. Digging, I excavated some glass plate slides, wrapped in cellophane. Several file cabinets contained the best preserved paper material. Before deciding to simply hand them down in their entirety, I leafed through them. I found a folder of children’s drawings. I handed them down to Jethro, who it turned out was their author.

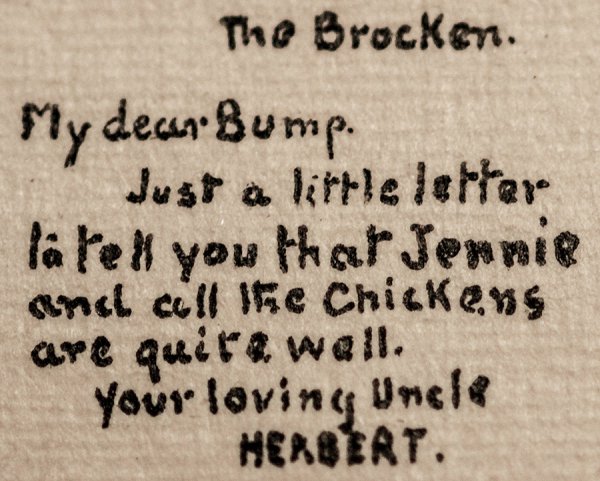

Among the papers, I found a Christmas card painting sent to Mary by Charles Burchfield in 1933, letters and ephemera from Ananda Coomaraswamy, a folder of letters from Alice Lewisohn, much material related to The Sunwise Turn, and – the gem, for me – an unbelievably charming letter which Herbert had sent to Mary’s four-year-old son, inscribed in a space smaller than a postage stamp in the center of a page, in such precise, miniscule text that it couldn’t be read without a magnifying glass.

|

|

Material encontrado en las ruinas de The Broken: una foto del primer emplazamiento de la librería

The Sunwise Turn de Nueva York y la carta de Crowley dirigida a Bumper.

A December 1937 letter to Mary from Alice Lewisohn, by then Herbert’s ex-wife informed her that “I received this week a shock that has been like a terrific blow. Bertram died last Saturday [3]. It’s still utterly incredible – we never ceased to have a profound relationship with all the varying changes life brought.”

Another letter to Mary from Alice dated October 29, 1946 shares the good news that “Bertram’s comics are now gathered together at the Metropolitan Museum in the print department.”

The experience of uncovering these letters and weaving together the threads of this forgotten life seemed to have come to a deeply fulfilling full-circle, beginning with the blurb in Dan Nadel’s book describing Crowley as a veritable phantom, and an “information gap.”

An exhaustive biography and art compendium of Crowley’s work is slated for publication in fall of 2017. New discoveries are still being made. Just a few months ago, an art dealer in London uncovered two gorgeous Herbert Crowley sculptural works from the early 1900s, produced in collaboration with the famed ceramist Pierre-Adrien Dalpayrat.

Who knows what other great works might be hidden in plain sight, or buried among forgotten files? Herbert Crowley was, as his creations clearly show, one of the true visionaries of early 20th century art – and yet, when the 20th century ended, he had been completely and utterly forgotten. All it took to unearth him was the care and attention of a small band of researchers, and a lot of persistence -- the willingness to follow every loose end, to knock on every door, call every phone number, and climb into every attic. How many other great discarded geniuses could be rescued this way?

For now, I’m just proud to have played my part in recovering the lost magic once wielded by the strange sorcerer known as Herbert Crowley. I urge you to seek out his work, and absorb its frightening, awe-inspiring majesty. It will enrich your spirit.

And may the revival of interest in Crowley’s work remind you that what’s lost does not always stay lost. Sometimes, with luck and effort, fallen beauty can be restored.

Bibliography

Nadel, Dan (2006): Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900 - 1969, Abrams.

Jenison, Madge (1923): Sunwise Turn: A Human Comedy of Bookselling, E. P. Dutton & Company.

Cabot Reid, J. (2001): Jung, My Mother and I: The Analytic Diaries of Catharine Rush Cabot, Daimon Books.

Birnbaum, M. (1914): Catalog of an Exhibition of Drawings, Paintings and Grotesques by Herbert Crowley, Berlin Photographic Company.

___________ (1960): The Last Romantic, Twayne Publishers.

Lewisohn Crowley, A. (1959): The Neighborhood Playhouse: Leaves from a Theatre Scrapbook, Theatre Arts Books.

Maisel, Edward y Griffes, Charles T. (1943): The Life Of An American Composer, Alfred A. Knopf.

[1] The Armory Show is the term commonly used to refer to the International Exhibition of Modern Art that took place between February 17 and March 15, 1913. This exhibition became a turning point for the United States Art in the direction of the so-called "modern art", against the hitherto dominant academicism. It caused American artists to become more independent and create their own artistic language (Tanslator's note).

[2] An explanation of the meaning of its name could be "it wags exaggeratedly".

[3] Bertram was the affectionate name he usually referred Herbert Crowley (Translator's note).